“Both familiar and not”: A glance at fear through the audiovisual language

Lucas Pereira Preti, José Rubens Leal, Aleksander Ernandes, Bruno Escudeiro.

Keywords: language, audiovisual, cinema, horror, fear, uncanny, unheimlich, cognitive disfunction, liminal spaces, paranoia, apophenia, The Shining

“Here is the final truth of horror movies: They do not love death, as some have suggested; they love life. They do not celebrate deformity but by dwelling on deformity, they sing of health and energy. By showing us the miseries of the damned, they help us to rediscover the smaller (but never petty) joys of our own lives.”

― Stephen King, Danse Macabre

“The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is fear of the unknown. These facts few psychologists will dispute, and their admitted truth must establish for all time the genuineness and dignity of the weirdly horrible tale as a literary form.”

― H.P. Lovecraft, Supernatural Horror in Literature

1. Introduction

2. The definition of fear

3. The history of the horror genre

4. Fear in genres other than horror

5. Silent film and non-verbal fear

5.1. The Shining’s non-verbal horror

6. Tools for fear

6.1. The uncanny valley

6.2. Cognitive disfunction

6.3. Liminal spaces

6.4. Paranoia and apophenia

7. The writing of the screenplay

8. The short-film

1. Introduction

The goal of this paper is to study the usage of the audiovisual language to create fear in the audience. A secondary goal is to produce a short-film to elicit such emotions, without resorting to verbal or written language, or any culture-specific signs.

For that end, we will explore the manifestations of fear in human nature, and its previous uses in other audiovisual works, be they formally defined as “horror” or not.

Fear is a primary emotion that results from the aversion of threats, and it is present in all “superior animals” 1 . “Horror stories have always made part of human’s collective imaginary”. Therefore, it’s no surprise “the pleasure of feeling and eliciting it” is such a staple of cinema since its beginning. “The fascination caused by these works are mainly explained [by it] dealing with subjects that culturally inspire some apprehension, such as nightmares and the fear of death” 2 .

2. The definition of fear

“The word fear comes from the latin metus” that refers to “an acute disturbance before a real or imaginary threat or risk. [...] It also refers to apprehension that something undesirable will happen. It is one of the “primary emotions”, present in all “superior animals” (and, therefore, in man). There are many ways to define fear:

"In a biological perspective, fear is an adaptive scheme that builds a survival and defence mechanism, that allows the individual to respond quickly and effectively in face of adverse situations. For the neurologists, fear is a normal response from the primary cortexes, through activation of the amygdala located inside the temporal lobe. From the point of view of psychology, fear is an emotional state, necessary so the organism can adapt to its medium. Related to the social and cultural aspect, fear is part of a person’s or social organisation’s character; through this perspective, it is possible to not feel it 3."

Paulo Dalgalarrondo 4 said “fear is not a pathological emotion”, but “a state of progressive anguish, increasing powerlessness in face of the inevitability of something we want to avoid.” For this author, fear can scale to gradually larger and larger proportions, which can be divided into “six phases, according to its extent”, starting with “prudence” (1); then “caution” (2); through “alarm” (3); and “anxiety” (4); reaching “panic” (5); and “terror” (6).

According to Márcio Bernik, director of the Laboratório de Ansiedade (Anxiety Laboratory) on the Psychiatric Institute of USP, a little known characteristic of human being is we like to feel fear. He explains that “our mind is so complex, it can associate dread to something completely opposite to it, like pleasure”, because “the intensity of fear” illicits physical responses, “like sweaty hands and pounding heart, but the feelings, thoughts and emotions associated with it are conditioned. Therefore, it’s possible to turn stimuli from horror into something positive”. For Armando Rezende Neto, phycologist from Unifesp, “the appeal of horror movies is great because human beings search, instinctively, strong and primitive emotions, and fear is the first one of these” 5.

Carlos Primati said:

"To watch a horror movie is to feel overly human, to attest to our physical fragility and the ephemeral character of our existence, it is to be alive. Because, similarly to a roller coaster ride, the greatest emotion is to get to the end, safe and sound. To read about it is an even more enriching experience, is strengthens our character and turns us less frightful; because those who, instead of facing their fears, hide themselves under their sheets in search for temporary safety, are the ones who suffer more. The horror-movie buff may be, from all the cinephiles, the one who most appreciates life 6 ".

3. The history of the horror genre

If we search for the “conception of horror as a genre, regardless of art form and medium”, we will find “in myth and religions [the] first source of raw material for artistic creation of this kind”. It is from mythology that terror comes to literature and, from there, to cinema.

The book The Castle of Otranto, from 1764, by Horace Walpole, is considered by some the first gothic novel in history. Half a century later, in 1818, the first great horror classic was written, Frankenstein, by Mary Shelley. “Taking many ingredients from myths and the Bible”, this sort of literature was “a basic inspiration to horror cinema in its infancy” 7 , still in the XIX century.

Although there are diverging schools of thought, it is widely agreed that the first horror movies were the short-films of director-magician Georges Méliés; Le Manoir du diable, from 1896, being the first of them. The first literary adaptations to cinema happened shortly after, in the first decade of the XX century. That decade alone saw Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1908, and Frankenstein in 1910. Countries like “France, the United Kingdom, the United States and Germany” were “the most notorious in the first batch of horror films" 8 .

The genre grew through the 1930’s, when it was “completely dominated” by the famous North-American studio Universal, who invested in the “ascension of the monsters”, with the most famous icons: The Mummy, Frankenstein, Dracula, The Wolf-man, etc. In the 1950’s, however, partially due to WWII, there was a steep decline in genre fiction, when American and Japanese filmmakers focused on “man-made monsters”. “The Return of the Fly, The Giant Gila Monster, The Alligator People amongst many others, helped with the ridicule of the genre”. In the 1960’s, things were looking better, with the English company Hammer going through its “golden age”. Besides that, “directors like Bergman, Polanski, Wyler, Aldrich, Clayton, Powell and Hitchcock realised the secret for success was in the human psyche” and “how insanity scares us” 9 . Also of note from that era are Bava, from Italy, and Mojica Martins, from Brazil.

The 1970’s and 1980’s continued without much exploration of the horror genre until, in 1984, North-American director “Wes Craven brought terror into our unconscious in the shape of a ripper wearing a red sweatshirt, killing teenagers in their dreams”. It was also him who, in the 1990’s, “revitalised the slasher with his metalanguage [in] the best horror franchise in horror history: Scream” 10 . “Many horror franchises fiddled with the mind of the teenager”, but Scream had “the prowess and boldness to play with its own genre”.

The XXI century “came with great ideas and new concepts” and “The Blair Witch Project, by Sánchez and Myric, displayed its terror with the most palpable tool one can imagine: marketing”. To this day no other horror movie has "worked on its own story in such a convincing way” 11 . As time passed, however, the necessity for the genre to evolve was clear. Watching monsters seducing its prey, atomic paranoias or cosmic threats wasn’t as impactful as it once was. The horror genre seems to evidence different social conditions. The secret appears to be in asking what scares us now. “Spirits? Religious fundamentalism? Hooded youngsters looking to take our property? The fragility of the family? The answers are singular, of course. But the problem is continuous” 12 .

4. Fear in genres other than horror

Horror movies are not the only ones to use suspense, fear and similar primitive emotions to arrest the spectator. Other genres too make use of these resources, and one can find many examples of such. We studied a few films that showcase how fear was always a tool in the bag of filmmakers.

In 2001: a space odyssey (undoubtedly a science-fiction film, according to the producers and critics), there is a scene where, to save his own life, astronaut Dave, played by Keir Dullea, is forced to turn off the spaceship computer, HAL 9000. Given the personification of Hal throughout the film, and the long time the audience has spent familiarising themselves with him as another human being, the scene is perceived as a murder, shown under Hal’s voice begging for his life. Dave commits this “murder” methodically, following numbered steps on the wall. There’s a sense of triviality to the life being taken, of indifference to the despair of the victim, and banality in the act of killing, making the process almost trite. All these feelings are unquestionably rejected by society and to conjure them (specially in a context of inevitability, and necessity for the survival of the protagonist) causes extreme discomfort, which absolutely qualifies the scene as befitting a horror movie.

Similarly disturbing scenes are easily found in many other non-horror movies. In the final climax of Raiders of the Lost Ark, a family adventure film, the faces of the villains are disintegrated, melted off with extreme violence and shot in extreme detail; highlighted by the agonizing screams of those faces.

Even in supposedly infantile films, such as Bambi, there can be found reaches for primitive human emotions, particularly in a scene that elicits in its target audience (young children), the same effect horror movies intend to. On it’s original release, Bambi was harshly and publicly criticised by psychologist Louise Bates Ames, a specialist in child psychology and pedagogy. She writes “possibly their worst fear is they would lose their mother, or father, [...] It’s a movie in which a child loses its mother and there is no resolution. The mother (is just) gone,” (Fountain, 1996).

This common use of these tools brings into question the solidity of the horror genre as a genre. A great example of this is Martha Marcy May Marlene, by Sean Durkin. According to its official website the film belongs to the genres Thriller and Drama. However, British film critic Mark Kermode classified it as a horror film. According to Kermode, the film “does exactly what a horror movie should do, it makes you feel honestly uncomfortable” 13 . Sometimes, these tools appear in science-fiction “when the Earth is threatened by aliens”, “fantasy and supernatural genres [...] can be confused with horror when they deal with revolting, horrific acts” 14 . The act of classifying films into genres, ultimately, appear to be arbitrary.

5. Silent film and the non-verbal fear

Our project entails the writing of a screenplay without any dialogue, in an attempt to make the film effective to spectators from as varied a set of contexts as possible. This choice brings us closer to the silent film, even though we will feel free to use sound as we wish, ie. soundtrack, music and folley. “The staple of silent cinema is in its expressivity and its power of communicating emotions and feelings”, since are the actors, “through body language and facial expressions”, who “give meaning to the silent film, telling us about the characters and their stories” 15 .

“The non-verbal communication expressed through gestures, posture, body orientation, physical appearance, facial expressions, etc.” are, Andrade says, “behavioural manifestations that relate to the individual and social context of the speaker” 16 . This corroborates with he idea that emotions, like fear, are culture specific. However, still quoting Andrade, “some gestures are universal and are always related to meanings that transcend cultural aspects.” There are “gestures and emotions considered basic”, like “happiness, sadness, anger, surprise, discuss” and fear itself. All these emotions have “a character of universality, not only in its manifestation, but in its recognisability”. Focusing on the “non-verbal act”, exploring “camera movements, framing and the soundtrack”, silent films enabled “their characters to be understood”, even outside of the culture in which they were made 17 .

5.1. The Shining’s non-verbal horror

To understand how fear can be elicited without the resources of dialogue and other expressions of language, our biggest reference was The Shining, from 1980. Even though there is dialogue throughout the film, there are also entire sequences that deliberately avoid it. The director Stanley Kubrick, in an interview with Michel Ciment, commenting on the restrictions of conventional cinematic storytelling, said stories are told “primarily through a series of dialogue scenes”, he continued: “most films are really little more than stage plays with more atmosphere and action.”

"I think that the scope and flexibility of movie stories would be greatly enhanced by borrowing something from the structure of silent movies where points that didn’t require dialog could be presented by a shot and a title card. [...] In my view, there are very few sound films, including those regarded as masterpieces, which could not be presented almost as effectively on the stage. [...] You couldn’t do that with a great silent movie" 18 .

This idea can be seen expressed in The Shining. The films is divided into segments, separated by title cards that describe events (“THE INTERVIEW”), or periods of time (“ONE MONTH LATER”, “TUESDAY”, “4 PM”).

One of the most impactful scenes have zero dialogue: the camera is close to the ground, looking down a hallway; at the end, there is an elevator. It opens and blood starts gushing down through the hallway, and doesn’t stop until it gets to the camera and obstruct its vision. Blood, as an icon is usually powerful, signifying pain, suffering, or death. But, in the context of the scene we just described, it obtains another meaning. The spectator is left wondering whose blood this is and how it came to be extracted from them. The spectator’s imagination is always more powerful than what the film explicitly shows, because the audience, collectively, branches the question into a thousand answers, one for each spectator 19 .

6. Tools for fear

6.1. The uncanny valley

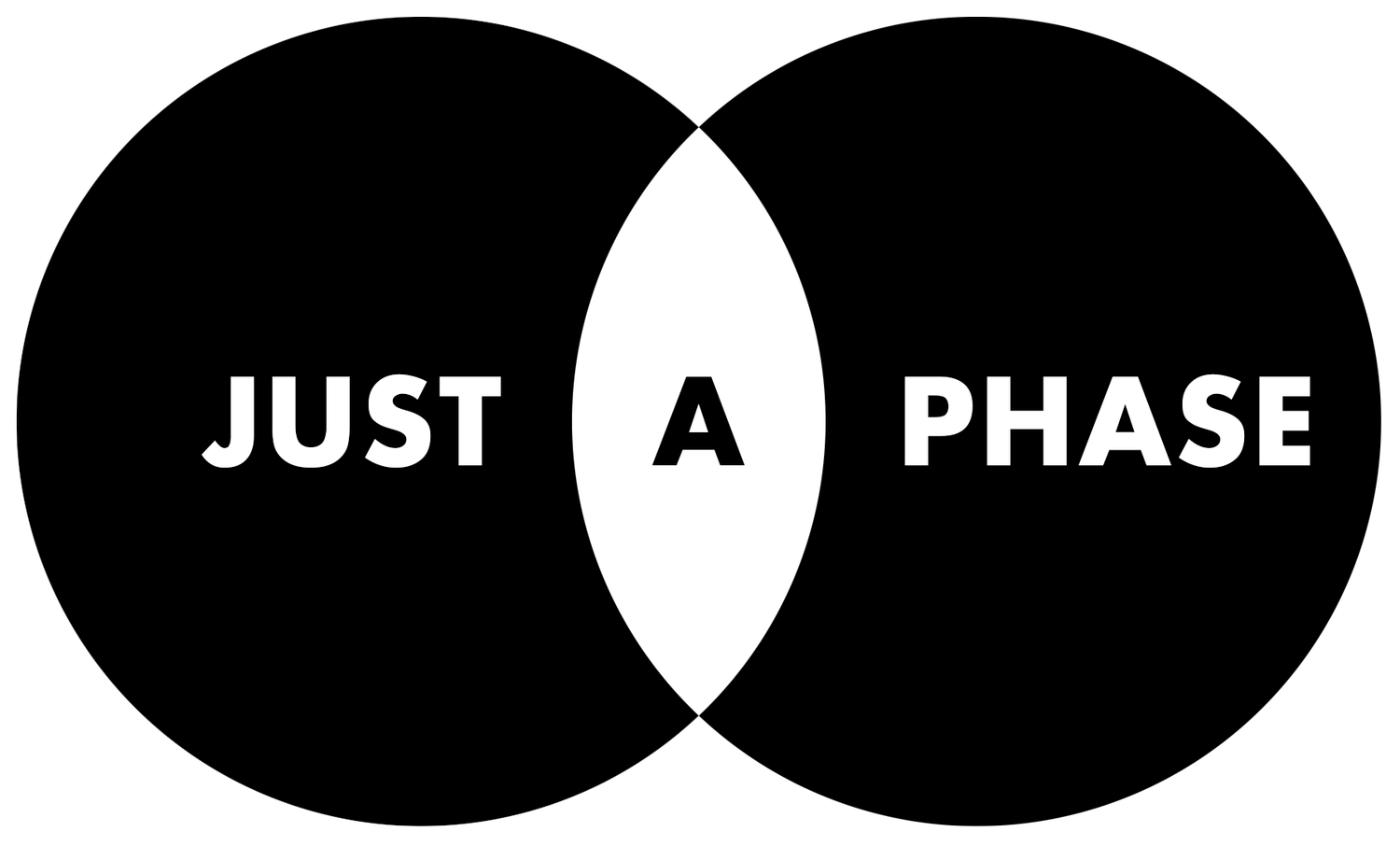

The “uncanny valley”, a word coined by roboticist Masahiro Mori, is a hypothesis in the field of robotics and 3D animation that suggests that when replicas of humans behave very similarly (but not identically) to real human beings, they create an unnerving effect on observers.

Figure 1: The uncanny valley

As a robot designer, Mori (1970) graphed what he saw as the relation between human likeness and perceived familiarity: familiarity increases with human likeness until a point is reached at which subtle deviations from human appearance and behavior create an unnerving effect. This he called the uncanny valley20.

An explanation for the deviation in the graph (Figure 1) may lie on what Sigmund Freud called Unheimlich — coined in 1906, by Ernst Jentsch, which can be translated literally as “unfamiliar”, or conceptually as “unsettling” —, relating to an unsettling feeling that follows the uncertainty of the existence of danger, or of the nature of said danger. Although Freud deviated from Jentsch, he agreed on his ideas on the ambiguous and the uncanny, and would later redefine Unheimlich as “the class of frightening things that leads us back to what is known and familiar” 21 (Freud, 1919:2). He argued that the uncanny comes from the ambiguity between the familiar and the unfamiliar, which leaves one uncertain as to how to react, to respond. Claude Lévi-Strauss said that masks are unnerving because they hide a part of that body that, in social interactions, reveals one’s emotions and intents 22 .

The simple showing of characters of objects that classify as in the uncanny valley is an easy way to extract its effects in cinema, particularly in the horror genre. Also, many films utilise the ambiguity or uncertainty of danger to elicit dread or fear. Good examples are the antagonist in Mama (figure 2) or, more subtly, the girl in The Exorcist (figure 3), where the distortion of the characters face is itself part of the plot.

The ambiguity between the familiar and the unfamiliar can be extrapolated into any object the camera is pointed to, and it was very subtly utilised by Stanley Kubrick in The Shining, where the decision to shoot actor’s faces with a wide angle lens (specifically an 18mm) resulted in a very subtle distortion of their faces23.

Mori’s experiments also relate a relation between movement and verisimilitude. Much of the nature of life is perceived through motion, and an interestingly and quick way of creating unnerving movement is to record it backwards, and reverse it in editing. David Lynch famously shot an entire sequence of the TV show Twin Peaks like that, including dialogue — and compensating for it with normal folley. Lynch commonly uses the familiar and the unfamiliar in his work, not only visually, but also narratively, which places his films somewhere in between a conventional narrative and experimentalism.

Figure 2: “Mama”, directed by Andrés Muschietti.

Figure 3: “The Exorcist”, directed by William Friedkin

6.2. Cognitive disfunction

The term cognitive disfunction is used to describe a “discomfort that results from two contradictory beliefs”. It was originally conceived by psychologist Leon Festinger, who “suggested people have a deep necessity for their beliefs and behaviours to be consistent. Inconsistent or conflicting beliefs lead to inharmony, which people fight hard to avoid”. According to him, “when there is a discrepancy between beliefs and behaviour, something has to change, to reduce or to put an end to the dissonance 24 ".

The word “dissonance” signifies a simultaneity or succession of two or more unharmonious sounds, an incoherence, an unpleasant combination of elements 25 . It didn’t take long for the audiovisual language, having to deal with overlapping, simultaneity and sequence of ideas 26 , to explore this creatively.

The images and the soundtrack are naturally overlaid elements in audiovisual language and their dissonance was explored, again, in Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining. Throughout the film, the choice of using one of the elements — image or sound — to jarring effect was consistently combined with the “silence” of the other. Examples are large orchestral hits when nothing visible changes, or quick crash zooms in total silence. In the opening credits. The opening credits of the film shows a beautiful lake surrounded by mountains, over which we hear threatening low frequency synthesisers 27 . In Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, a torture scene is combined with the jolly “Stuck In The Middle With You, by Stealers Wheel 28 . The setting for Steven Spielberg’s Jaws is a nostalgic small beach town in the summer, filled with happy families.

6.3. Liminal spaces

The idea of liminarity 29 is generally attributed to the anthropologist Arnold Van Gennep who, “studying primitive societies, identified the different categories of rituals that result in a change in social status, which he grouped together in a general category of ‘rites of passage’ 30 . He identified a three-fold structure in which separation from the initial social group and incorporation into a new group frame or delimit the intermediate liminal phase. This corresponds to a phase of uncertainty, transition, imprecision, without any defined framework, and is thus sometimes dangerous 31 ”.

A liminal space is a place that embodies the unsettling nature of the in-between. There is a correlation to be made with the Unheimlich. The nature of liminality is, by definition, undefined — and, therefore, unpredictable. It falls into the social equivalent of the uncanny valley. This was explicitly the premise of Stephen King’s The Gangoliers, which is essentially “an airplane inexplicably lands on a deserted earth”. Everything else is normal, except there are no people, and no life. The simple absense of people seems to drag some locations — those that are commonly crowded — into the unfamiliar enough for them to fall into the uncanny valley, and photographers have taken advantage of this in making unsetling images32.

The author maight have been thinking of this when he spoke of there being three types of terror:

"The 3 types of terror: The Gross-out: the sight of a severed head tumbling down a flight of stairs, it’s when the lights go out and something green and slimy splatters against your arm. The Horror: the unnatural, spiders the size of bears, the dead waking up and walking around, it’s when the lights go out and something with claws grabs you by the arm. And the last and worse one: Terror, when you come home and notice everything you own had been taken away and replaced by an exact substitute. It’s when the lights go out and you feel something behind you, you hear it, you feel its breath against your ear, but when you turn around, there’s nothing there… 33 ”.

“We wanted the hotel to look authentic rather than like a traditionally spooky movie hotel, [...] The hotel’s labyrinthine layout and huge rooms, I believed, would alone provide an eerie enough atmosphere. This realistic approach was also followed in the lighting, and in every aspect of the decor it seemed to me that the perfect guide for this approach could be found in Kafka’s writing style. His stories are fantastic and allegorical, but his writing is simple and straightforward, almost journalistic 35 ".

Commenting on his film The Sixth Sense, director M. Night Shyamalan made a similar remark 36 .

6.4. Paranoia and apophenia

A most relevant tool was the idea of paranoia — both from the character’s part and the audience’s. Although there wasn’t much formal research done on it, it was surprisingly important in the construction of the screenplay. Our biggest references were Rosemary’s Baby (Polanski, 1968), The Thing (Carpenter, 1982) and The Conversation (Coppola, 1974).

When put in a defensive position, feeling intellectually threatened by the film, the spectator tries to foresee the course or the plot. This results in an added charge or meaning to any information they are given, which can be exploited to cause what psychiatrist Klaus Conrad called Apophenia37, the tendency to perceive meaningful relationships between random things, making the amount of information the spectator receives arbitrarily large.

7. The writing of the screenplay

Maybe more than anything, the screenplay was an effort to orchestrate (and fight against) the audience, be it in an unconscious level, of physiological responses, or a conscious level, of simple anticipation of the plot. We chose, also, to attack the masculinity of the men in the audience38, putting the protagonist into a state of powerlessness as often as possible.

It’s important to highlight that the screenplay was written with cinematography and editing ideas very much in the foreground, it was written as an audiovisual experience.

8. The short-film

This paper was written through 2016 and early 2017, and translated into English in 202039. The film was shot and edited in early 2017, and is now available on Vimeo.

Endnotes

If you see nothing here, everything is working as intended.

-

MURALHA, Edson Moraes. Os sentimentos e suas Emoções. Publicado em 19/02/2016. Disponível em: https://www.wattpad.com/272322545-os-sentimentos-e-suas-emo%C3%A7%C3%B5es-capitulo-v-a-coragem. Acesso em 13/03/2017. ↩

-

GHIROTTI, Joaquin. Filmes de Terror. A História dos Sustos na Sétima Arte. Publicado em 10/04/11. Disponível em: http://www.spectrumgothic.com.br/gothic/cinema/filmes_terror.htm Acesso em 13/03/2017. ↩

-

Conceito de; March 15th, 2012, disponível em: [...]…]...]http://conceito.de/medo]. Acesso em 14/02/2016. ↩

-

DALGALARRONDO, Paulo. Psicopatologia e Semiologia dos Transtornos Mentais. Porto Alegre: Artmed, 2000. ↩

-

LOIOLA, Rita. Entenda por que gostamos de sentir medo. In: Revista Galileu. Publicado em 28/12/2009. Disponível em: http://revistagalileu.globo.com/Revista/Common/0,,EMI113919-17579,00-ENTENDA+POR+QUE+GOSTAMOS+DE+SENTIR+MEDO.html. Acesso em 13/03/2017. ↩

-

PRIMATI, Carlos. In GARCIA, Demian. Cinemas de Horror. Editora Estronho, São José dos Pinhais/PR, 2016. ↩

-

SANTIAGO, Luiz. Plano Crítico. Apontamento sobre o Terror no Cinema. Publicado em 01/10/2015. Disponível em: http://www.planocritico.com/apontamentos-sobre-o-terror-no-cinema/. Acesso em 29/03/2017. ↩

-

SANTIAGO, Luiz. Plano Crítico. Apontamento sobre o Terror no Cinema. Publicado em 01/10/2015. Disponível em: http://www.planocritico.com/apontamentos-sobre-o-terror-no-cinema/. Acesso em 29/03/2017. ↩

-

LEHNEMANN, Andrey. A evolução do medo no cinema de terror. Publicado em 12/01/2017. Disponível em: http://dc.clicrbs.com.br/sc/entretenimento/noticia/2017/01/andrey-lehnemann-a-evolucao-do-medo-no-cinema-de-terror-9298481.html. Acesso em: 29/03/2017. ↩

-

LEHNEMANN, Andrey. A evolução do medo no cinema de terror. Publicado em 12/01/2017. Disponível em: http://dc.clicrbs.com.br/sc/entretenimento/noticia/2017/01/andrey-lehnemann-a-evolucao-do-medo-no-cinema-de-terror-9298481.html. Acesso em: 29/03/2017. ↩

-

LEHNEMANN, Andrey. A evolução do medo no cinema de terror. Publicado em 12/01/2017. Disponível em: http://dc.clicrbs.com.br/sc/entretenimento/noticia/2017/01/andrey-lehnemann-a-evolucao-do-medo-no-cinema-de-terror-9298481.html. Acesso em: 29/03/2017. ↩

-

LEHNEMANN, Andrey. A evolução do medo no cinema de terror. Publicado em 12/01/2017. Disponível em: http://dc.clicrbs.com.br/sc/entretenimento/noticia/2017/01/andrey-lehnemann-a-evolucao-do-medo-no-cinema-de-terror-9298481.html. Acesso em: 29/03/2017. ↩

-

KERMODE, Mark. Mark Kermode Martha Marcy May Marlene [...]video]. Publicado em 05/02/2012. Disponível em: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jlnEudznsw0. Acesso em 01/04/2017. ↩

-

DIRKS, Tim. Horror Films. AMC, FilmSite. Disponível em: http://www.filmsite.org/horrorfilms.html. Acesso em: 01/04/2017. ↩

-

ANDRADE, Leilane Lima Sena de. A expressividade do cinema mudo na construção de significados. In: Distúrb Comun, São Paulo, 26(1): 95-100. Março, 2014. ↩

-

ANDRADE, Leilane Lima Sena de. A expressividade do cinema mudo na construção de significados. In: Distúrb Comun, São Paulo, 26(1): 95-100. Março, 2014. ↩

-

ANDRADE, Leilane Lima Sena de. A expressividade do cinema mudo na construção de significados. In: Distúrb Comun, São Paulo, 26(1): 95-100. Março, 2014. ↩

-

CIMENT, Michel. Kubrick on The Shining An interview with Michel Ciment. Disponível em: http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/interview.ts.html. Acesso em 02/04/2017. ↩

-

In a further level, the spectator may remember the information that the hotel in which the film is set was build on top of a Native American cemetery, which may evoke the horror of the Native American holocaust. ↩

-

MACDORMAN, Karl F. and ISHIGURO, Hiroshi. The uncanny advantage of using androids in cognitive and social science research. Available at http://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/10a4/df9911f3e4de090b16a0b6279acee7f8ad52.pdf ↩

-

FREUD, Sigmund. The Uncanny. 1919. Available at http://web.mit.edu/allanmc/www/freud1.pdf. Accesed on 03/04/2017. ↩

-

LEVI-STRAUSS, Claude. The Many Faces of Man. In: World Theatre, 10, 3-61, 1961. ↩

-

From an interview with actress Shalley Duvalle https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hFPmTV_UqKA ↩

-

CHERRY, Kendra. What Is Cognitive Dissonance? Available at https://www.verywellmind.com/what-is-cognitive-dissonance-2795012 ↩

-

as beautifully demonstrated by Lev Kuleshov in his experiments: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_gGl3LJ7vHc ↩

-

from the Latin word līmen, meaning “a threshold” ↩

-

Van Gennep A., 1909.– Les rites de passage. Étude systématique des rites, éd. Picard. ↩

-

FOURNY, Marie-Christine, The border as liminal space, available at https://journals.openedition.org/rga/2120 ↩

-

An example: https://marypearson1.wordpress.com/tag/liminal-spaces/ ↩

-

https://www.goodreads.com/quotes/84666-the-3-types-of-terror-the-gross-out-the-sight-of ↩

-

Given his dislike for this cinematic adaptation of his novel ↩

-

CIMENT, Michel. Kubrick on The Shining An interview with Michel Ciment. Available at: http://www.visual-memory.co.uk/amk/doc/interview.ts.html. ↩

-

Although we couldn't find the original quote, unfortunately. ↩

-

CONRAD, Klaus (1958). Die beginnende Schizophrenie. Versuch einer Gestaltanalyse des Wahns (The onset of schizophrenia: an attempt to form an analysis of delusion). ↩

-

taking a queue from "Alien" screenwriter Dan O’Bannon: https://plotandtheme.com/2016/05/18/the-xenomorph-and-the-perversion-of-sex-in-alien/ ↩

-

Feel free to correct me on the translation ↩